What are Singing Sands?

Singing sand dunes (also called "booming sand dunes") are exceptionally rare dunes of sand that emit an audible acoustic reverberation when the actual grains are disturbed or moved.

How many singing sands or booming dunes are there?

It is estimated that there are only about 30 of these dunes in the entire world.

Beaches with more moist climates boast "singing sands" of their own, where the sand will "squeak" when you walk through it. These are much more common, and are not the same as the booming dunes, which I also refer to here as singing sands.

( I will try to differentiate by calling the more common kind "squeaking sand".)

Where are they located?

The rarest and most special ones can be found in some of the world's driest climes. The largest concentration of singing sands is in the state of Nevada in the U.S. Singing sand dunes can also be found in California, the Namib Desert of Africa, Abu Dhabi, the United Arab Emirates, inner Mongolia, Chile, China, and Morocco, among others.

A listing of some of the world's singing sand sites can be found here.

How do the sands make sound?

Movement will make the sand emit sound. The movement does not have to be great, as any motion that produces "shearing" (think of a sand-avalanche) will be able to create sound. Anything from a car moving down the slope of the dune (not recommended!) to moving your fingers through the top layers of singing sand will produce an acoustic reverberation.

Why do these dunes emit sound and others don't?

This depends upon a number of factours, and scientists are still working to understand the exact conditions under which singing sands exist.

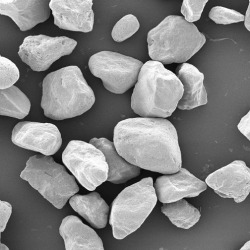

One known factour is the size of sand grains at specific locations. The grains at the world's most prominent booming dunes are defined as being medium-grain, in addition to being well sorted.

Another is movement. All sound-producing motion, regardless of how strong, seems to follow an "avalanche" pattern of shearing.

Another important factour is that of humidity. Most booming sands are about 0.1% humidity. Dunes with humidity levels of 1% will reverberate, but the sound is weak at best. The drier the better, as far as sound production goes.

Lab tests by scientists have been quite interesting in this respect. When sand from booming dunes was put into a jar and taken off-site, the acoustic properties of the sand remained so long as the humidity remained the same as at the actual site from which the sand was taken. However, if any moisture was either added or removed, the sand produced no vibration whatsoever.

Can I slide down the dune and make the sand sing?

Of course! Particularly if you're one of those odd types that actually likes having copious amounts of sand in your underwear. By all means, be my guest.

Do singing sands actually produce musical notes?

Absolutely. This has been scientifically measured at singing sand locations across the world. The dunes at Mar de Dunas in Chile produce F, while those at Ghord Lahmar, Morocco are G sharp. A low C (about two octaves below middle C) have been heard at Sand Mountain in Nevada, although sometimes it fluctuates to a low B and even C sharp.

Why does reverberation continue for some time after movement of the sand stops?

It's difficult to say, and the geomorphologists and other scientists cannot yet fully explain such phenomena.

Can booming sands make sound on their own?

Yes. Some singing or booming sand dunes can emit sound without human intervention. In places like the Gobi desert, for example, desert winds alone can be strong enough to produce audible vibration. In these cases, the "singing" is like a low hum that ebbs and flows with the winds.

There are instances where sands can shift due to forces other than wind (shearing, slippage, or "avalanches" that can be caused by earth tremors or other forces), which will cause the sands to sing seemingly of their own accord.

What is the study of singing sands called?

The official term is called "Aeolian Research", but the study of singing and booming sands also overlaps into the categories of geomorphology, morphodynamics, and geophysics.